Transformation

There are many ways to personal and societal transformation. Sometimes it is dramatic and involves other people or situations that change our lives, for good or for worse. Sometimes health or employment issues change the course of our lives and sometimes we go down in flames, because of our own actions and poor judgements. Sometimes we rise again….or not. The one constant reality is that we cannot escape transformation. It is part of our nature and that of the larger cosmos. Bringing this universal concept closer to home, I ask, “Can two people, in a committed relationship, go through the changes and chances of this fleeting world and remain faith-full?” We have limited the meaning of faithfulness to sexual fidelity, but it can mean more. Some people have the ability to remain faith-full, while many of us, cannot. Our faith cannot be limited to a belief in God either. Do we simply trust the powers and forces behind the universe and the strange twists and turns of fate, or not? How can we experience fullness of faith in ourselves, each other and the universe?

Our relationships, more than any other human experience, reflect the dances of coming and going, growing and decaying and some artists have captured the deeper truths about what life constantly provides. I think of the New York artist, Ross Bleckner, who has been fascinated by decay and transformation and was one of the artists who survived the AIDS epidemic to try to make sense of it. I found a quote by Bleckner helpful to describe the physical destruction of death “When someone dies, a library is burning” and used it at many of the funerals I have conducted over the years.

Bleckner painted silver trophies, sometimes levitating towards heaven to describe the constant stream of loss as beautiful, talented and loving human beings were taken from us pre-maturely by AIDS and prejudice. In the early 1980’s, if you were diagnosed with AIDS, managed to dodge the weight of discrimination and sheer terror about this disease, you had about 9 months to get your life in order before a certain death. The health care system was not your friend either. Two images help me think about this dark period of history, still difficult to write about. One is Bleckner’s trophy paintings, the other is an icon that seems to follow me and appears at times when I am looking for answers to unanswerable questions. I had no idea the icon would become so important as I glued her image on a piece of wood and stained it to look like an antique icon painted on wood 40 years ago.

She has been in every home I have ever lived in, crossing seas and continents. Art has a way of speaking to us, as this icon has spoken to me in very different contexts and ages of my life. She is also cheap and fake, made out to be something she isn’t. Yet, she still possesses a power that gets my attention. Like our images of God and Christ, they are cheap representations of the real thing. Icons have a particular story in the history of art and usually are never written by one person, so there is something collective about them. They are mirrors into our own souls and this one particular icon, although it has not changed significantly in my possessions over nearly half a century, it has marked significant moments in my journey as a gay priest. The most recent appearance of this icon was in St. Paul’s Chestnut Hill, (a sometimes familiar wink from the mystery we call God) as I was discerning a call to be their Interim Rector. There she was, on one of the altars, present and looking out at all of us. The Madonna and child gaze out at us, reflecting back our own tormented questions, with nothing to say. The sceptic or atheist may dismiss this encounter as co-incidental. Faith-full people see it as crumbs under the table when so many of us are hungry for bread and meaning.

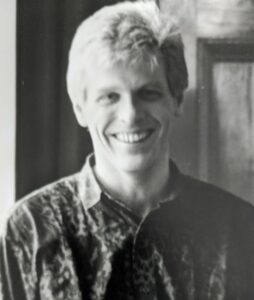

In the beginning, the icon was made by sticking a photograph onto wood and varnishing it so it looked “old”. In 1977, it lived with us in our little home on Colin Mountain overlooking Belfast as Frank and I dodged getting outed in Belfast. She moved with us to St. Mary’s Lodge in Ballsbridge, where she hung on a wall that heard our cries and angst when we were finally outed. A Franciscan friend inadvertently over breakfast one morning, shared the news to my boss, John Neill, that we were a gay couple.

I was suspended from all duties and brought before the Archbishop of Dublin, Henry McAdoo, who was to decide my fate. The choices he gave me were either to break up with Frank and continue at St. Bart’s as a celibate gay man, or resign. McAdoo confessed he had no experience of gay issues or knew any gay people, enough to ensure he “could not recommend me for any work that might involve young people”. Although my former bishop who ordained me, Arthur Butler and George Simms, (the former Archbishop of Armagh and head of the Church of Ireland) were sympathetic and as supportive as they could be as individuals, the episcopal culture permitted no outside interference in another bishop’s jurisdiction, so our fate was determined.

Frank and I had visited San Francisco and Los Angeles the previous year and found ourselves light years away from the Victorian sexual mores of Ireland and the U.K. We stayed with my friend from university, Nigel Hamilton who had just married Mary Mail, another seminarian at Church Divinity School of the Pacific in Berkley, California. Mary’s insight later helped to soften the blow that Frank and I were destined for different roads. “It was clear from your visit with us Frank was an English tourist, looking for something interesting to do on vacation while you happened to be an American born in Belfast in search of a home.” My unconscious connection of ordination and continuing ministry outside of Europe had not surfaced at all during that final year in Dublin. It was still inconceivable that Frank and I would break up, we would be outed in Ireland and loose our home and friends. It was also simply inconceivable I would end up working in the USA.

So, we continued to live as best we could in Dublin and unable to find work as an art historian, Frank joined a government-sponsored training program to become an accountant. Jobs in the art world were even in less demand in Ireland in 1980. We made some new friends in Dublin and attended one of the underground gay clubs that emerged in the late 1970’s like “Flikkers“. I just discovered during in my 2021 interview with Edmund Lynch for the National Library of Ireland’s LGBT archive, that one of the clubs had the Eurovision Song Contest’s stage set had been dismantled by RTE’s joiners and prop makers from the studios and moved to make our gay club look inviting! Good for RTE, our national television network for equipping Dublin’s underground gay club!

I worked on many community projects outside of my usual parish work, especially with young people and reconciliation. I was part of the Church of Ireland Youth Council and met a young journalist called Sheila Wayman who interviewed Frank and I in two church publications. We remained anonymous, given it was still illegal to be gay in the Republic and my work in the church. We were pushing the boundaries as much as we could, and the anonymous interview was candid and one of the first in the church where the subject was even discussed. When we were outed, John Neill joined some of the missing dots and figured out the interview was about Frank and I.

I resigned as assistant priest at St. Bartholomew’s in April 1982, during Holy Week. Although completely suspended from all clergy functions, I, with Frank, had three months to say goodbye, move house and start anew. Returning to London seemed the best we could do as the Church of Ireland had basically blackballed me from any employment on the island. We both began looking for work with the help of friends like Gilbert Hopley, my former Chaplain from Bangor, and Christopher Spence, someone we met through the lay co-counselling movement. The parish was apparently divided over John Neill’s handling of the situation. The lack of transparency and compassion was augmented with an inability to say goodbye and have closure, so the wound would take years to heal on all sides. Given the St. Bart’s congregation had many LGBT folk and progressive inter-faith marriages, my sudden dismissal was not good optics for a congregation where the acceptance of divorcees or mixed marriages (Catholic/Protestant) was proudly promoted.

A new beginning

Frank and I limped to London. Losing everything in Dublin would have an even greater toll on both of us after the exile. Our relationship of five years would now be tested and the fallout of St. Bart’s would take many years to settle. I applied for a job as Youth Director for the British Council of Churches and was qualified enough to get the appointment. Another job looked promising utilizing my teaching credential in the London Borough of Newham in the East End of the city. I interviewed for both. Newham provided buildings and community organizing for the immigrant communities coming from Uganda, the West Indies and trying to counter the deep racism in British society. The “Out of Work Center” (an unfortunate name) was the local education authority’s response to the high rate of school dropout and unemployment among British youth of west Indian descent. They worked closely with an interfaith religious network Newham Community Renewal Program, headed by Rev. Paul Regan, a Methodist minister, so the teaching credential and church leadership experience all helped to get me this interesting job. Archbishop MacAdoo’s comment at my exit interview with him haunted me. He could not recommend me for any work with young people (without cause). Being gay was simply enough to label me a pedophile. I thought it prudent to come out to the British Council of Churches’ General Secretary and explain why I left St. Bart’s. The follow up interview was brief and he informed me they were withdrawing the job offer. I had my letter of acceptance for the Newham job in my jacket pocket and mailed it just outside the fashionable Eaton Square headquarters of the Council. The church had done it again! It would take two more years for me to consider doing anything priestly. As far as I was concerned, my relationship with the church (other than working for a religious organization in Newham) was over.

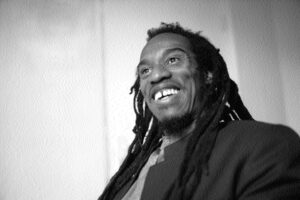

Frank and I made a down-payment on a house in Tottenham and he found work as an accountant. The work in Newham was difficult and I met some wonderful people through the Center. The police were always dropping to keep an eye on the young people who dropped in and socialized there. An active Co-op nearby attracted alternative leadership, including the future Poet Laureate, Benjamin Zephaniah who expresses much of the frustration and mistrust people of color in Britain have bravely faced for generations. The Times included him as one of the top 50 post-war British writers and he was a regular supporter of the work we were doing at a sensitive time just after the Brixton uprising in 1981.

As much as I enjoyed working among and learning so much from the young British/West Indian community (especially about the power of solidarity in the face of institutional racism) I was deeply unhappy and restless over the next two years. I saw how these young people, against all odds, had each other’s backs and the ghetto, for all its limitations, protected the soul from being completely destroyed. These experiences in East London pushed me to find a place where, as an openly gay man, my soul might survive. and maybe even thrive? These young people and leaders like my associate, Arlene, had amazing courage and fortitude that ignited a deeper longing for community and liberation. Britain in the early 1980’s was not only deeply racist and homophobic, but it was also anti-Irish. Margaret Thatcher epitomized neo-British Imperialism, crushing the northern mining communities and going to war with Argentina over the Faulkland Islands. I shared the feeling of my Black friends that England was my Babylon too.

Frank and I settled in and began fixing our house and making new friends in London. He was active in the gay movement and went on some of the early gay marches to celebrate Pride. Yet, something was missing and we both began to see other people. Two people in particular, changed the course of our lives and we met them over the same weekend in Amsterdam during an Easter break in 1982. Frank met a Greek diplomat who worked in Brussels, and I met an American called John Upchurch. Constantine and Frank saw each other for a couple of months between London and Brussels. We were clearly drifting apart. John was from Atlanta and living in California. He was on vacation in Amsterdam when we met in a restaurant quite near to the street captured in my Amsterdam at night painting. Our lives would never be quite the same again. When I look at that painting, I cannot help imagining the conversations going on behind those windows over 400 years of existence, wafting out over the hustle and bustle of the Amsterdam canals. I reflect on the hap-hazard ways we all seek transformation, through love, betrayal and hope for something to save us.

John invited me to spend a month in Laguna Beach (which would become the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic in California because of its large gay community). We attended my first Gay Pride parade in Los Angeles. It was at Pride that I met Marsha Langford, the President of Integrity USA, and she told me the bishop of Los Angeles and the Pasadena-based headquarters of Integrity were looking for a priest with a youth background to work with runaway and throw-away youth. These kids were part of a generation of mid-western and rural kids rejected by (often) religiously motivated families and communities, simply because they were gay, lesbian or transgender.

I found a sympathetic priest in Laguna Beach, Bob Cornelison, who was willing to help me with the immigration paperwork and offer me a position at St. Mary’s where I could begin to function again as a priest. Although this would take over a year to figure out and would involve a move from London to California, it was one of the most difficult years of my life. After all we had been through, all the hopes and dreams seemed t0 vanish as Frank and I finally parted after 7 years together. I moved to the USA in November 1982 after my Green Card was approved. The first year was very difficult. Everything was new and American culture was very different to what I was used to.

Frank came to visit me in California and Mexico and we both hoped for some form of reconciliation, but something else was at work. My first year in the USA had been very challenging and I was dependent on a few friends for support and accomodation. Frank was still living in our house in London and it looked more and more unlikely that we would get back together again. The two relationships that had moved us out of our “stuck” period did not last long either.

In 1983, I met my second partner, William Monsour, and he helped me with the difficult transition of living in Los Angeles and finally establishing myself here as Youth Director of the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center in Hollywood. The Episcopal diocese of Los Angeles took a little longer to license me to function as a priest, but life began to take on a whole new shape, thanks to many friends and Episcopalians who took me in. I remember being offered the position by Steve Schulte and Jody Curley and feeling I had to check in with Bishop Rusack that he had no objections to one of his clergy working in a gay organization. To his credit, he backed me (in 1983, there were only two openly gay clergy in Los Angeles at the time, Malcolm Boyd, the writer, and Fr. Bill Leeson). Something else was at work that restored my lost confidence im myself as well as the institutional church. Weekends were spent in Laguna, attending church and preparing for another hard week with the street kids of Hollywood. I began to experience something of the solidarity I had been privileged to witness in the Black community in London and to see how the church was integral to the challenging journey of LGBT liberation. Work at the Gay and Lesbian Center was difficult and we saw about 30 new street kids a month (all victims of a homophobic “throwaway” society). We provided shelter, support, help with getting off the streets when they were ready, and began the slow removal of barriers to allow LGBT foster parents to be finally recognized by the state and local government. We were able to get grants from the State to work with high risk LGBT youth, opening the first LGBT youth shelter and foster care program in California. With Bishop Rusack’s support, I began my ministry again and I expanded my spiritual base from Laguna to St. Thomas church in Hollywood, just a mile away from the center of LGBT survival prostitution on Sunset and Santa Monica Boulevards.

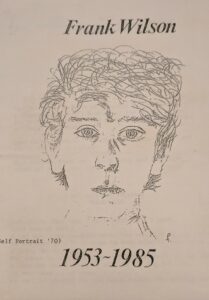

In April 1985, on Easter Monday, our friend, Malcolm Macourt, called me to tell me Frank was in Hammersmith Hospital diagnosed with the lung disease that characterized an AIDS diagnosis. Working at the center of the gay community in Los Angeles had exposed me to the emerging needs of the community and many of my street kids were getting sick with AIDS and needing services, but I never imagined it would come this close to home. I immediately returned to London and spent two weeks with Frank and his family and there was so much we did not know back them and he taught us all so much. I assumed I was also HIV positive and went to Belfast to tell my parents what was going on. It was all a slow motion surreal trainwreck. My father had reacted negatively to the news of being outed in Dublin a few years earlier and never wanted to see Frank again in his home. He got his wish. Now everyone was waiting for the other shoe to drop. Later, William and I found out we were HIV negative by taking the newly created and infamous HIV test. Initially the gay community discouraged the test on the grounds it was “a test for blood and not for people.” We were living in a twilight zone where people began to disappear and Frank’s diagnosis was a complete shock to all of us and AIDS marked the beginning of a new era, for us and the wider world community. All of this was still hidden from us as we stumbled in the dark, trying to be faith-full. I wish faith was about certainty, as is commonly believed. But faith is the opposite of certainty.

Christopher Spence was particularly helpful with Frank as he was dying and both Christopher and I remember sitting on the floor of his apartment in London, knowing our lives were to radically change because of our relationship with Frank and this terrifying disease. After returning to London from Belfast, I said goodbye to Frank just before he went into a coma. He had tubes down his throat and could not speak. He used a speaker -board spell out his final words to me. He quoted a line from a song by Foreigner “I loved rediscovering you and I always will.”

Frank asked Christopher to make sure he heard the song on headphones as he passed away: “I want to know where love is”. Devastated and not able to do anything but pray and cry, I found my way with Christopher to the hospital chapel. There on the wall was that same icon I had mentioned earlier. She looked at me cold and silent as I sobbed, still not believing Frank was dying. “I hope one day, this will all make sense because it doesn’t make sense right now”. That’s what I asked her as Frank passed away on May 1st 1985. That was my prayer. Like a beautiful sparking trophy in Bleckner’s painting, Frank left us heavenward, to be followed by so many, so many… beautiful people. I returned to Los Angeles and life would never be the same again. Three week’s later, following an internal personnel crisis at the Gay and Lesbian Center, the Executive Director was terminated by the Board and I was appointed Acting Executive Director. The Center was literally in the middle of the growing AIDS storm that had been quietly brewing, but a handful of people there were taking it seriously. “We are a gay organization, not an AIDS organization,” was our idiotic defence.