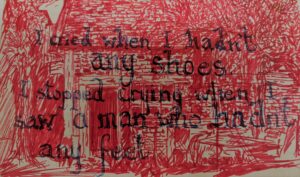

An ink drawing of a homeless shelter in Troyes, France where I spent part of a summer. “I cried when I hadn’t any shoes. I stopped crying when I saw a man who hadn’t any feet.”

I was very influenenced by living in an ecumenical and interfaith community in Troyes, France where I worked during the summer of 1971. There, I met my first Muslim, had eucharist with Catholics and met my first Catholic Worker priest, Fr. Yves. I needed to improve my French and finally passsed O Level French, required to qualify me for the British University system. It was a remarkable adventure and I returned with my friend from Grosvenor, Ian Dawson, who had bravely journeyed with me all the way to France! I passed my French examination! We lived in the homeless shelter, sponsored by the very active international faith community called “Coppainville” until we found work for the summer to support ourselves. Coppainville would train and send young advocates for peace and reconcilation all over the world, especially to places where there was conflict. I met members of this community in Belfast and was invited to visit the mother community later that memorable summer.

The artist as trickster and truth teller

As a teenager, I fantasized about becoming an architect and would spend hours drawing imaginary buildings, designing imaginary towns and palaces from early sketches of farmlands that would be erased and substituted with roads and early town planning. My skills of imagining places and projects that did not yet exist, were quietly being honed using imagination and the trickery of drawing. Art and drawing are as much about imagination as they are about trickery and illusion. The artist is both a technician and a trickster who makes the observer believe the chicken-scratches and colors on the page resemble something or someone, known and tangible. The art itself is not a photograph but a recognizable representation or it can be completely abstract, tickling the unconscious. Art can have something to say or convey. It shares a god-like capability (inherent in the human being) to create and develop something out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo).

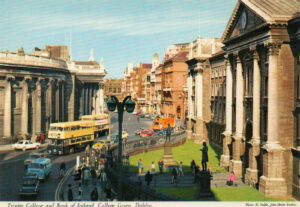

With art, most people usually prefer to recognize a face, a building or to capture the spirit of a place. Always, it is an interpretation, yet most people usually like a piece of art to be more recognizable than representational. This beginning love affair with architecture is also reflected in my early photography. I have a few early photos of grand and ancient Dublin buildings (from a day trip in 1970). The urban myth in Northern Irish working class loyalist communities was that Dublin was full of barefoot peasants, while the cultural/religious and economic links to the United Kingdom has ensured a better standard of living in the North of Ireland. I was completely surprised by the beauty of Dublin, its wide streets, Georgian terraces and noble institutions like Trinity College and St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Maybe people were misinformed or lying about other facts, i.e. “God hates gay people”?

Travel, showing up and finding out for oneself what was going on, became an important quest for reality and truth during those teenage years. Getting out of N. Ireland for a while was itself an education. There are some things you can never learn at home.

From that first 100 mile trip to Dublin, travel became a trusted educator with architecture and art becoming a measure of civilization and culture. Art and architecture opened up my sense of confinement and misinformation – keys to other forms of self-discovery, not least, my awakening as a gay man. My love of Dublin and the people of the Republic of Ireland, Irish art and literature, shaped me profoundly, right up to the present day. A few little glossy photos in my archive remind me of that early awakening as a 16-year-old in search of a place to belong and to find inspiration. It has not left me. A recent visit to Dublin and the West of Ireland in 2021 simply confirmed what this teenager encountered back then. Life would never be quite the same again. Reflection on this process of self-awareness and self-realization, how to discern truth and reality from propaganda or reinforcing social norms, is a central theme for anyone involved in communication or education these days. If we have an under-educated and isolated population in any segment of our national or international life, democracy is weakened and its alternatives of theocracies, autocracies and totalitarianism, sparkle in the eyes of the marginalized masses. I reflect on our lack of attention and investment in education and equal opportunity in the USA as a root cause of the growing divide in the country and we are now reaping the fruits of decades of neglect, namely, ignorance and an inability to tell truth from falsehood.

The USA and the world is now dealing with FAKE NEWS on an unprecidented scale and the artist, like the journalist, has to communicate what he/she are actually seeing and feeling, based on what is real. Art can be co-opted by any side. Fascism has always used art and architecture as propaganda and a way to prop up their ideology and nationalism. Yet, Fascism has also been terrified of the power of art to expose its distortions and feared the artist or the writer in significant moments in history. I think about why the “Degenerate Art” exhibition organized by the National Socialists in Germany became so important, or the book burnings of writers and scientists like Magnus Hirschfield (the leading sexologist of his time) adventing the Second World War.

Art became something to own, plunder, and censor. We sometimes forget Hitler was a frustrated architect and artist who cried at Wagner operas and imagined a glistening Berlin with its wide boulevards and epic public buildings from which Germany would govern the world for a thousand years! Hugo Boss ensured the German army would look and feel good in their designer clothes. We forget about the carpeted offices, fashionable suits and dresses, with manicured and painted nails that signed off on and bureaucatically orchestrated the mass destruction of Europen Jewry. The artists, writers, journalists, pastors and homosexuals who threatened this new world order would also be deemed un-patriotic and anti-Fatherland. They too must be isolated and silenced. There must be one narrative only, at any price.

Artists can use or misuse their gifts as trickster and truth-teller. It is easy to be co-opted, bought and sold. Supporting and really valuing the artist, writer, journalist and scientist, as they mirror back to us our own discovery of who we are and how we are connected to each other, will be vital in the years ahead if we are to enjoy the cherished freedoms of democracy and give hope to those who aspire for another way. Without them and their collective vision and critique “the people perish“. When we forget or ignore our history, we usually repeat it.

A sabbatical from “The Troubles” in N. Ireland

Like so many teenagers growing up in N. Ireland during “The Troubles”, many of us used the British and Irish university systems to get away from (what would become) a 30 year sectarian civil war. I recently watched Kenneth Branagh’s movie, “Belfast” and he captures the despair of a society that was once fairly integrated but within a few weeks, Catholic and Protestant neighbors petrol-bombed each other into the ghettos that still divide the city.

It was not surprizing to read the statistics in 2014 that teenagers in N. Ireland were statistically more academically motivated than other teenagers in the U.K. The report also hi-lited the growing inequality of the educational system and the impact of poverty on academic achievement and “levelling up” (a recent political phrase to put a different spin on the growing economic inequalities in contemporary Britain). This phenomenon was given impetus in the 1970’s and 80’s when many of us were in our own forms of “lock-down” because of the sectarian violence and militarization of social controls in n. Ireland. We simply had no-where to go and had lots of time on our hands to study in the hope we could go to university outside the province.

Some of us would return after three or four years of study elsewhere, as I did, but the great brain-drain that impacts all the little countries of Europe (and Eastern Europe in particular)began in earnest in the 1970’s and the movie “Belfast” captures much of the family and community trauma that these exiles experienced. The deep loyalty to place, family and community runs deep and it is challenging to give that up and start all over again, as many of us had to do. Exiles also had to deal with jealously and resentment from family and friends when we might return to a deepening despair .”Sure, there’s nuthin here” was a frequent phrase that summed up the resignation between exile and those who remained. In my own family, my father, (similar to the dad in the Branagh depiction of divided familiy life) wanted to emigrate to England and worked there sporadically over many years, while my mother wanted to stay in Belfast, beause it was all she knew. The picture of the cousins at a birthday party (above) describes part of that deep family connection that people valued more than exile. University provided a via media for a generation who wanted to work at healing many of the broken aspects of N. Ireland’s dysfunction -its weird and unique politics and its oppressive sexual politics, both sides of the border. Women friends are amazed at my recounting stories about life in Dublin in the 1980’s when women has to buy “pencils” to get contraceptives (given the Catholic church had banned all forms of birth control in the Republic of Ireland). Pencils provided the cover for families to plan their own destinies and be able to get contraceptives, as strange as this may seem to us all today! Abortions were illegal and shipping young women off to Britain for a shameful abortion was very much part of our culture. The Irish gays and lesbians shared the same boat trip of hidden shame-Ireland always exported her problems abroad rather than dealing with them, until relatively recently. Today, while Ireland moves forward, recently changing marriage and abortion laws, America flirts with theocracy and the abortion issue is one of the litmus tests of our failing democracy. Same-gender marriages may be the next target?

At 18 years old, and with three long years of sectarian violence becoming the new normal, University College, in Bangor, North Wales, Trinity College, Dublin and London’s University’s Institute of Education afforded five years away from it all. I returned home to Belfast regularly during this time, sharing in the terror and fear of being blown up at any moment while simply walking down any street with parked cars. One of them might explode without warning. The city center was fenced off like modern -day airport security perimeter, where everyone was searched before entering. Security checks by the police and British army assured one was never quite at ease. Security cameras were everywhere and the terrorized people of Northern Ireland became the guinea pigs for future government surveillance on a scale yet unknown in post war Europe. The church was part of the problem and I believed, had something to contribute to the solution. So I continued to work with young people from both sides of the sectarian divide, utilizing communities like Corrymeela, where Protestant and Catholic kids could get to know each other outside of their segregated schools and walled ghettos.

Beyond these academic structures and preparation for a career in the church, I created a few sketches and some religious-themed designs. Two sketches remain of the University of North Wales Bangor, (where I studies theology in preparation for ordination to the Anglican ministry) and a pencil sketch of a carved wooden angel from our college chapel (printed on card-stock to raise money for the college organ).

The Anglican chaplaincy at Bangor

I designed an altar frontal for the college chapel, representing the spiritual gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit (lots of tongues of inspirational fire), lovingly sewn by another student preparing for ordination. Remnants of the frontal were worked into my ordination stole, based on the Coventry Cathedral Cross of Nails, made by Patsy Wilson, my first partner’s sister.

Following the Nazi bombing of Coventry Cathedral, the dean of the cathedral came across three medieval iron nails that formed a cross in the middle of the burned out ruins. It became a symbol of European reconciliation after the Second World War and a clear mission for a new 20th century cathedral, built on the site of the destruction. The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, forgiveness, new life and hope could have a significant message for Europe as it repaired itself from the madness of war. Could this message work for Ireland? Art and symbolism could inspire people to do the impossible. Combined with a theology that restrained itself from demonizing or being weaponised by nationalism or homophobia, maybe art could bring out something better in all of us? We all needed the fruits of the Spirit -love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, self-control. No law could create these, reminded St. Paul. What might in-spire us to be different? What might inspire us to love others and even love ourselves?

Frank Wilson

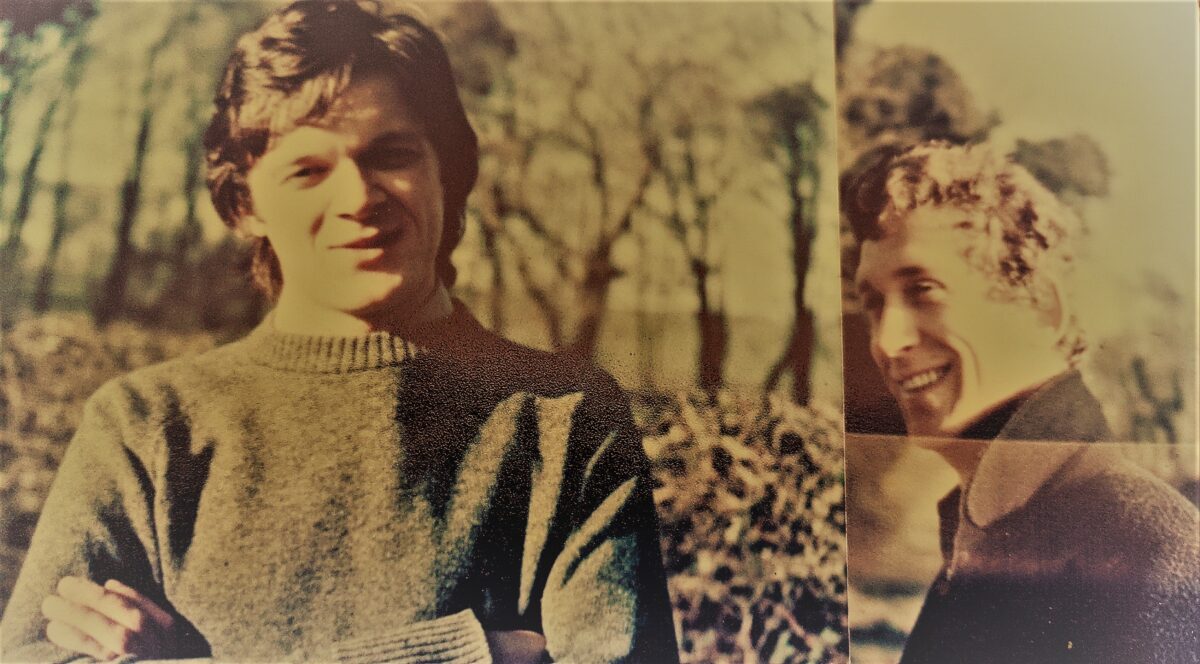

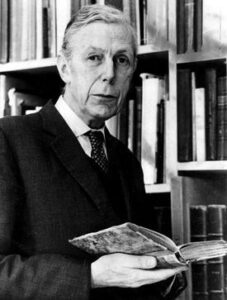

Frank Wilson was to become one of the most significant people in my life since we first met in Durham in January 1976. Frank was preparing to attend the Courtauld Institute in London, accepted to study Art History under renowned professors like Sir Antony Blunt (the Queen’s Portrait Curator) and as we discovered later, was a spy for Russia during the Cold War.

Blunt was a closeted gay man, who like many upper-class English homosexuals in the 1920’s, longed for decriminalization of homosexuality and a different world order that tried to breach the economic divide. Blunt was outed as “the fourth man” joining infamous spies like Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean who were part of this “Cambridge Five” spy-ring. During his three years at the college, Frank had no idea of Blunt’s history. Blunt’s true identity was unknown until 1979, when he was exposed and stripped of his knighthood. Blunt’s story is an interesting slice of what life in the first part of the 20th century looked like for gay people who were overshadowed by draconian laws from the end of the 19th century when homosexuality was criminalized. Many of the 76 countries where it is still illegal to be LGBT adopted similar legislation as British colonies. Thirty eight African countries, many former British colonies, still advocate criminalization, fully supported by the churches and in particular, the Anglican church. I commend the work of Maurice Tomlinson with Anglicans for Decriminalization . It is hard to believe in 2022 this is still impacting so many millions of LGBT people and their families!

Blunt was from the upper crust of British imperial society with a direct link to the Queen through his academic knowledge of art, but his homosexuality was a deep threat and left him and many open to blackmail and subversion. In 1954, the year I was born, 1,000 gay men languished in English prisons because they were victims of these laws and attitudes. Frank’s generation would benefit from the law reform movement that started in the late 19th century with the fearless work of Edward Carpenter and others, finally to come to fruition in 1969 when homosexuality was decriminalized (not in N. Ireland until 1982).

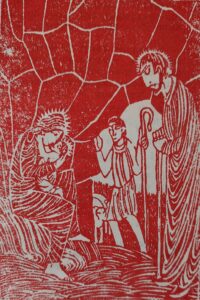

Frank was himself an artist and two examples of his work are in my care -a beautifully executed paper marquetry of Durham Cathedral (a love gift to me) and one of his fun Christmas cards, a lino-cut of the nativity based on (Eric Gill). Life with Frank was totally life-changing. Not only were we a gay couple, living and working in Britain (and for a time in Ireland, where it was still illegal to be gay until 1982) but Frank introduced me to Florence and Rome and the wider world of art and its history.

Frank specialized in the painters and sculptors of the Renaissance. We spent several summers travelling throughout Europe and learning about the great painters and their techniques. I wasn’t very active in my own art in those days, but a few sketches and lots of photographs remain.