Preface

Art continues to be a major vehicle for my humanness. Coming out and seeing the role art has played in my journey is not an obvious part of my story to many who know me. Activists don’t have time for things like ART! Nevertheless, I hope my own revisiting some inner spiritual forces that inspired my activism and gave me some inspiration to get through some pretty hard times, may be of help to others.

Over a couple of weeks, explore this part of me with me. The art part of me needs more air and can no longer remain in a closet. Our lives are sometimes creative and we long for creativity, in ourselves and others. Who knows where this may take us.

Chapter 1. Early influences

Coming Out as an artist

Applying paint to a canvas demands commitment and courage. There is something important about the butterflies in the stomach as the blank page invites the artist to boldly BEGIN. A continuous inner conversation goes on –“I can’t do it.” “People or a person won’t like it.” “Will this do, or would anyone want to own this?” “I want to fix something I painted years ago, but should I just leave it as I saw it back then?” These questions and prompting to intervene or make acceptable to others (rather than to oneself) are part of the artists spiritual development and integrity. Even with success, the artist can simply coast on past works, merely repeating what “sold” rather than keep pushing one’s own boundaries and experiences. Art is a process of continually coming out, pushing beyond ego and what others may think or feel. “Is it finished?” “Is it good..enough?” Am I finished? Am I good enough? We sometimes ask these questions of ourselves and our lives.

Although I have loved drawing, painting and designing spaces (and even furniture) most of my life, there has not been much time or commitment spent on these creative activities. During a very active ministry over the last 4 decades, these gifts were necessarily transformed into designing health care responses or human rights organizing to help integrate communities that struggle or are violent in response to minority differences. What I am still learning from integrating these two parts of my life, is the PROCESS of planning to design a chair or an AIDS Service Center, both follow design principles. Creating a painting also has a clear process where the subject can take on a life of its own and the artist begins an earnest dance with the subject. However, there have been more recent available times where I have found inspiration and solace in rediscovering painting, using recreational time in Fort Lauderdale, (away from parish work in New York or Philadelphia) to complete some playful paintings. I just shipped three of them off this week to Philly as another marker as I transition from working to retirement. I have spent more time painting in the past 6 months than I have in the last 60 years!

Many who know me may not even have been aware of this lifetime passion and gift. This interest was nurtured in me by my father, who was the first person to teach me to draw. He spent his life in construction and roofing and so this more reflective side of him was rarely seen, but he would sometimes draw military aircraft or decorated family mirrors for the Christmas holidays with snow-covered churches, fir trees and Hallmark scenes.

I continued to develop these early explorations in school, under a range of art teachers, especially Rosalee Saunderson who was an art teacher at Grosvenor High School in Belfast. Rosy was one of the few teachers I felt a deeper connection with. She would sometimes retreat to the art supplies closet of her classroom where she would smoke during lessons (while the class was carrying on with a project!). This unusual disclosure between teacher and student also allowed both of us to share our complicated lives and relationships with each other. Looking back, these conversations allowed for pastoral support and personal conversations that I would value later as a priest. I am sure both issues (smoking in class and a friendship with a student) were inappropriate, but she was very approachable, vulnerable, and gave me a sense of belonging in an alien and homophobic environment of Northern Ireland. School was also intensely academic and so art classes provided breathing space from the intellectual pressures of life back then. Rosalee was a great teacher and her friendship was more important than I realized back then. Art and the art closet where she would “light up” allowed us to be human and vulnerable.

Not much survives of my artistic endeavors from these early years except for two small pieces -one in oils of the head of an old man (Toscanini’s head, copied from an old magazine) and a charcoal drawing of the suffering Christ. Religion was beginning to interest me and by 16, when both items were created, there was a soulfulness and sadness about these pieces that probably reflected my own soul space back then as the Irish troubles dominated our exterior and interior realities.

When I was born in 1954, over 1,000 gay men were documented to be in prison in England. What has changed in my lifetime and what remains to be changed? Who knows how many LGBTQ languished elsewhere. Homosexuality also remained illegal on the island of Ireland until the early 1980’s. I remember searching in our school library for something to describe what I was discovering about myself, to no avail. Art became a spiritual lifeline that kept something beating in my being, although not fully appreciated or understood. My father’s generation saw art as recreational and not terribly practical. Art provided the snail-like shell of protection that kept me alive during these violent and homophobic years.

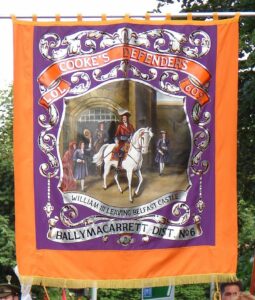

There is a long history of Ulster working class art, often displayed in religious or sectarian banners that would be carried in front of the Orangemen in their annual parades through the cities, or the now familiar paintings that dominate the gables of streets where I grew up. This street art has been politicized and often acts as tribal boundary markers differentiating Catholic/Republican or Protestant/Loyalist enclaves, augmenting the flying of nationalist or loyalist flags. Art and architecture were highjacked by a fundamentalist political/religious narrow culture that could easily suffocate the very air that a liberating expression of art offered humanity. Art and symbols are powerful when weaponized. Tribal connection, the interpretation of history and memory and propaganda in persuit of power have always been legitimate artistic currency.

Street art in Northern Ireland still flourishes, though in recent years, the dark militarization and romanticism of para-military armed patriots or loyalists dominating gable walls in east or west Belfast, actually look just the same with their black masks.

Chapter 2 -Beyond Northern Ireland https://albertogle.com/the-art-of-coming-out-chapter-2-beyond-northern-ireland/