The Reluctant Revolutionary?

A Lenten Pilgrimage in the Steps of Martin Luther: March 2017

A convergence of opportunities led to a surprising Lenten retreat 4,000 miles from home. It all centered around the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, and I felt I needed to give some background on Martin Luther (1483-1546) and on sites associated with him during last year’s six-week series “Sacred Sites” at St Peter’s, Lithgow. Last March, Charlie Pierce, (former director of the Morgan Library in New York) offered to lead an ad hoc group of sixteen parishioners to view an exhibition of some Luther artifacts never seen before in the USA. Again, my interest in the Reformation was piqued.

During the past two years, I have noticed that St. Peter’s has a high percentage of parishioners who are former Roman Catholics. As a result of our demographics, Rev. Cam Hardy and I have tried, beginning on Reformation Sunday in October, 2016, to weave into our sermons some of the Anglican and Roman Catholic similarities and differences. Most parishioners are unaware that

75 % of Anglican/Roman Catholic beliefs and practices are shared; nor do they know how our important and significant differences came to be. I am hoping that this coming year, as we celebrate 500 years of Reformation history, we develop a common understanding of Luther’s legacy for our own time.

Lutherans and Anglicans have a common history, liturgical life, and theology, more than, say we Anglicans have in common with Presbyterians or even Methodists. Episcopalians, (as Anglicans are called in the USA) are in “full communion” with the Lutheran church, which means we recognize one another’s ministries and share in the sacraments. It is possible for a Lutheran pastor to be appointed to an Episcopal Church position and vice versa. Many years ago, I had the honor of being invited to take part in the ordination of a Lutheran pastor through the “laying on of hands.” This is a significant ecumenical sign, and something we do not yet do with Roman Catholics (who still regard Anglican orders as irregular, even invalid). The Reformation created different understandings about the priesthood and the ministry of all the baptized, and these differences remain acute and challenging.

Even though I studied the Reformation a long time ago, Luther has remained an enigmatic figure to me. Was he a slightly deranged fanatic whose theology was used by the emerging European princes to break up the era’s “big government”—the Roman church’s imperial authority? The invitation to the Morgan Library exhibit and sharing these sacred German sites associated with Luther at St. Peter’s this past year, opened up a renewed interest in discovering who Luther was and how the Reformation shaped the church and world I know today. The definition of this revolution is described here:

The Protestant Reformation was the 16th-century religious, political, intellectual and cultural upheaval that splintered Catholic Europe, setting in place the structures and beliefs that would define the continent in the modern era. http://www.history.com/topics/reformation

So by January 2017, it looked as if my formal Christian Education opportunity for this year, should focus on Luther and the Reformation. Two of the key sites associated with Luther’s tumultuous revolution were within a few hours travel (by train) from Berlin, so I designed a six-day tour taking in Wittenberg (where the Reformation began) and, nearly two hours farther away, Eisenach, where Luther went into hiding from the ecclesiastical and civil authorities following his excommunication by the Pope.

A religious death threat

Excommunication meant that anyone could kill him without punishment, so the medieval Church had basically condemned him to death, a “sentence” brought about by his theology and for his attacks on the corrupt practice of selling indulgences to finance the local German and Roman Catholic churches (particularly the present edifice in St. Peter’s Square in Rome which began to be built in 1506 and completed in 1626).

It is difficult for anyone in our modern society to understand the power of a papacy that could effectively condemn someone to death. A recent analogy might be the fatwa issued by the Iranian government against Satanic Verses author Salman Rushdie, with a $600,000 bounty on his head. However, the papacy’s call ultimately backfired.

An economic revolution

There are many theories as to why this perfect storm—the Reformation— happened when it did. Why was Luther saved by one of the German princes? One theory centers on generations of German resentment toward Church taxation practices, which levied higher rates on Germany than on any other part of Europe; Luther’s challenge became a way of giving expression to this frustration. Such economic and theological divisions eventually fractured the entire Holy Roman Empire, resulting in a redefinition of the relationship between church and state (civil society).

Luther was in effect redefining the role of the state in the process of defending a fairly orthodox form of Christianity. He did not tolerate the theologically unsound practice by the Anabaptists of replacing infant baptism with adult baptism, but he felt the state should banish rather than execute them. He did not support the Peasants’ War (1524-25) when 100,000 peasants died, even though it was in part inspired by Reformation and biblical principles. Also, Luther’s public call to the princes to resort to the sword to keep law and order remains a blot on his legacy, illustrating how politically and economically conservative his Reformation really was. Yet his attempts at finding a via media, signifying moderation in all things, had a large impact on the Reformation in other parts of Europe, especially in England.

A direct link between Luther’s Reformation and the Episcopalian church can be traced to the fragmentation of centralized religious authority under Rome and the emergence of independent nation-states led to Henry VIII’s declaring himself head of the Church of England—our mother church. Henry had no scruples about using the sword to protect his own interests; nationalizing the church and its assets in England served his own imperial agenda, expanding his army and colonial interests in the New World and in Ireland.

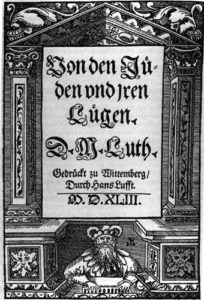

In the wake of recent global events like Brexit and a rise of nationalistic fervor versus globalism, during my trip to Germany, I became particularly eager to learn more about the last decade of Luther’s life, when his deep fear and hatred of Jews and Turks emerged.

Was he suffering from PTSD? What circumstances had led to these positions after a lifetime spent helping people rediscover the good news of God’s love and grace? I set out to understand more about Luther the man, the physical places he touched and how they shaped him, and the revolution he started. Were there any lessons to be learned for the 21st century as we go through our own revolutionary times?

I was delighted to discover that others were asking similar questions. Our friends at Union Theological Seminary in New York City convened a two-day conference last April on Bonhoeffer and Luther, specifically the positive impact of their lives on ours. This meeting occasioned conversations related to some of the deeper questions I had uncovered during my pilgrimage the previous month, questions that wove together a lot of personal strands, including my early commitment to reconciliation, which was shaped by sectarian (Catholic/Protestant) violence in Ireland. I had just had an opportunity to see how these divisions have impacted Germany over the last 70 years. Germany’s division and subsequent healing since the Second World War and the fall of the Berlin Wall remain important markers in a long history of religious and ideological conflicts. Luther’s anti-Semitism played a significant role in the German church’s co-option of fascism through National Socialism and the sites associated with Luther and the Reformation were inaccessible to West Germans until relatively recently.

So, I discovered this major educational component to the 500th anniversary of the Reformation as much for contemporary Germans as for the global faith community.

Germans are celebrating this anniversary as some Americans are seriously reconsidering constitutional separation of church and state as well as the role of the state in defending the (Christian) faith, so the 15th and 16th centuries have much to teach us. In May 2017, President Trump signed an Executive Order on Religious Freedom that appears to remove the wall between Church and state and allowing political endorsement of candidates and policies than before. How does a Muslim travel ban impact the privileges of Christians who appear to benefit from the proposed ban? As the world becomes more connected, the forces that divide and cause fear among races,

nationalities, or religions are once again being played out (just as they did via Luther’s anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim writings and cartoon illustrations, which were eventually reinterpreted by the Third Reich).

Our current generations must understand the role of “holy” violence in our shared history and identities. Has Luther anything to say to us that might give some hope or encouragement? Or do we need a renewed reformation that spins us into the next human orbit of history without making the mistakes of the past?

The journey begins

I arrived in Wittenberg on a Monday morning. Having had little sleep on the flight to Berlin and then a brief 40-minute train ride, I left my bags at my Airbnb residence, owned by a musical-instruments maker named Jorge Dahm. He had bought and restored a set of buildings skirting a medieval courtyard that had been used as a blacksmith’s shop. Twenty years ago, following the fall of the Berlin Wall, he moved to East Germany and invested in this community. He’d replaced the rotting support beams and most of the wooden windows and doors, creating a wonderful space for himself and his international visitors, most of whom, he said, come to learn more about Luther. When I arrived no one was present to give me a key, so I left my suitcase hidden in the bicycle shed and stopped in at a nearby restaurant, where I pointed to a picture of eggs and sausages to order my breakfast. The bar was smoke-filled, as locals chatted over morning coffee. The smoke clung to my jacket all day, reminding me I was no longer in the USA!

When the former East Germany was under USSR rule, the residents all learned Russian, and so few people here in Wittenberg actually speak English. As I walked around for some fresh air, waiting for my host to show up, it was amazing to think these wonderfully wide, elegant streets—deserted that Monday—had been patrolled by the Red Guard until 1991. What I saw instead was a sleepy, provincial town coming to the end of a multi-year project to spruce itself up for the millions of people who would want to do what I was doing. How had this little place, with its two main streets lined quaint churches and houses, taken on the most powerful institution in the world, the Church, and survived?

I began taking pictures along the main streets, which had been closed to car traffic since becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. I saw everything from sushi bars to foot massage services with fish tanks where you could put your feet for…fish therapy? In front of the grand town hall in Market Square stood the famous statue of Luther and his ally and friend, the younger Philip Melanchthon.

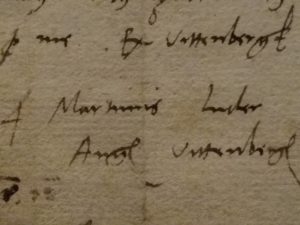

Both men were in their early twenties when they were hired to teach Biblical Studies at the brand-new university of Wittenburg. (The Elector of Saxony had been inspired by royal universities established by rival German princes.) Melanchthon was a genius in classical languages, while Luther, at the time an Augustinian monk, had just completed his doctoral studies in nearby Erfurt.

Both men remained committed to academic studies and the mentoring of young people throughout their time in Wittenberg. I visited the building, the Leuocorea, where they taught; it is still a branch of the larger regional university at Halle. Melanchthon and Luther always had numerous students living in their family homes, and down the street from the university was the house Luther lived in with his wife, Katerina, and their six children.

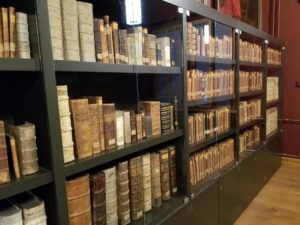

Luther became one of the wealthiest men in town, with his wife, a former nun, running a very busy beer business and investing in local real estate. Luther’s modest professor’s salary was augmented by these and other activities, including the proceeds from boarding and tutoring students, who would often keep records of the conversations at household meals. (What an opportunity for young people to sit at the feet of these great local heroes!) Both professors would have received stipends, and the university built a house for Melanchthon that still stands (and is open to the public) close to the university. I was impressed by the collection of books at both men’s houses.

The great humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam had a huge influence on them, and their personal libraries have hundreds of his works.

Erasmus clearly thought Luther and the German Reformation had gone too far with the reforms that would lead to divisions within Christendom. Eramsus may have seen himself as a mediator between Rome and the German princes as they fragmented and eventually ended up in armed conflict, exhausting the region. Scholarship that provided the intellectual underpinning of the Reformation was pivotal in this long conflict. In Wittenberg I could imagine the importance of an emerging university with Luther and Melanchthon as young intellectuals applying the new technology of printing to the spread of ideas. Through their pamphlets and the translation of the Bible into German, Wittenberg became the artistic, intellectual, and spiritual capital of the Reformation.

One of the highlights of my visit was going to St. Mary’s Church, located in the heart of the city, where both men preached and administered the sacraments, (pre- and post-Reformation) and where some of the first Protestant liturgical changes actually occurred. It was here that the chalice was first administered to the laity. It was here that the laity rioted against indulgences, broke statues, and intimidated priests for saying masses for the dead. It was here, too, that Luther and Katherine got married as monk and nun, uprooting the notion of clerical celibacy. These reforms and symbolic gestures of defiance had a profound effect upon the German people. Their marriage, an act of sexual revolution, was celebrated by the whole of Wittenberg with processions and parties for a whole week! Soon these events opened the floodgates of reform within religious orders, where much of the wealth and intellectual capital of the church was sheltered. Later, in England, Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries and major land grab would be softened by legislation permitting clerical marriages.

Luther’s war against indulgences—money paid to shorten a sinner’s time in Purgatory—was an article of his reform movement. At Wittenberg’s Castle Church, part of a former royal palace complex, Frederick the Wise held many thousands of holy relics designed to keep him out of hell for just over two million years.

Priests earned an important part of their livings praying for the dead, and Luther decided to engage the student community in a debate about the efficacy of relics and the Church’s power to sell indulgences—to the poor in particular. Luther thought that souls should be released from purgatory and eternal damnation simply as a consequence of faith. This would have been the most Christian thing to do, wrote Luther. Instead, the Church’s powerful infrastructure needed to raise thousands of gold sovereigns to pay off debts and purchase ecclesiastical titles and land. (St. Peter’s in Rome was under construction.) The combination of the exploitation of regional German electorates and an increasing resentment toward Rome due to indulgences and taxation gave rise to popular pietistic movements, which sought a more personal relationship to God than what the Roman Church offered, often for a price. This populist spirituality brought more attention to the intellectual work of Luther and Melanchthon outside of the university setting.

Occasionally peasants and students would hear from Luther and Melanchthon through sermons preached at St Mary’s or the Castle Church, where Luther had nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the front door (the university notice board on the Eve of All Saint’s Day, November 1st). Luther’s perfect storm depended more than a little on the threat of open revolt from the peasantry over economic hardship as their farms and businesses suffered. Luther may not have had the support of the peasants to carry through his reforms without these dire economic issues threatening the medieval power of local princes. He adroitly walked the tightrope between the conservatism of a medieval feudal society and its emergence into the Renaissance. He threatened civil disobedience if the princes did not live up to their responsibilities as good Christians obeying Christ rather than the emperor or the pope, while refusing to support open violence and rebellion, calling on these same princes to maintain law and order.

Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X in early 1521, after which Frederick the Wise led him into ten months’ hiding in Wartburg Castle. Subsequently he was invited to return to Wittenberg, where he had now to govern. (That challenge reminded me of the difficulties experienced by Rev. Ian Paisley, who in my own lifetime went from being a fiery Protestant theocrat to Northern Ireland’s First Minister. It was a remarkable conversion to a more moderate political leadership, and it cost him a significant number of his more extreme supporters.) So, in the course of his own personal journey, Luther became a bridge, forcing the papacy and Roman Catholicism to rethink its position in the world. Nothing was to be the same again.

During my week in Germany I reread Roland Bainton’s Here I Stand, a classic account of the life and legacy of Martin Luther. It gave me some helpful background to the places I visited in Wittenberg. In many ways the remaining thirteen years Luther spent there as a pastor, teacher, and political leader were an extension of the time he had spent in exile at Wartburg.

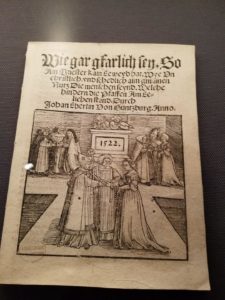

Revolutionary Art and Printing

His notoriety created a nearly unbearable double-edged situation: on one hand he was the former opposition leader who had returned home to lead a government torn within itself; on the other he was essential to that community’s role in shaping, for centuries to come, Protestantism internationally. Nonetheless his embrace of this particular confinement in Wittenberg, allowed him to focus on teaching at the university, translate both the Old and New Testaments, renew the liturgy, and write close to 3,000 significant tracts or sermons on a variety of reforms.

Throughout my visit, there was a sense of sacred space about Wittenberg, as it and the entire country prepared extensively and expensively to revisit the effects of this very local revolution, after emerging from forty-five years of atheistic communism under the Soviets. Many of the buildings were in disrepair. Millions of euros have been spent by cities like Wittenberg and Eisenach, and for many locals it is a jolting experience. At a recent meeting of the Town Council, the successors of Luther’s theocratic vision, municipal leaders were asked about what could come out of the 500 Year Celebration, whose planning had consumed them for at least a decade. The university had no plans to share students the close to 20,000 historic records and books from Luther’s time. The leaders had no plan for keeping young people employed, although one of the area’s major industries had opened a first-class interactive science center in the main square a week before my visit.

Luther had been the first academic to develop a system of religious education that taught people to be biblically literate and think theologically, and he had called upon the miserable sinners of Wittenberg to cough up four pence each to support the teachers and pastors who were ministering to them and their children. He was able to articulate a vision to carry out what he termed the “priesthood of all believers.” Luther and Philip Melanchthon reduced the seven sacraments (traditionally associated with the Church’s institutional control of people’s lives, that is baptism, marriage, ordination, confirmation, and holy unction at death) to an emphasis on two sacraments only -baptism and eucharist.

This theology also shaped Anglican polity in that so much of what Luther did was picked up by the English reformers when they came to translate the Bible, reform liturgy, and look at the relationship between the power of the princes (Henry VIII) and the church, reshaping both.

What is most astounding to me is the volume of writing this one man accomplished in his lifetime. Bainton notes that Luther’s work in translating the Bible into German was as of high a value as that placed on the works of Shakespeare with respect to the standardization of the English language and its literature. At the same time he completed bodies of work on the liturgy and Book of Common Prayer, early church music, and Christian education, especially for the young.

I was privileged to pay coincidental visit to two places associated with one of history’s great followers of Luther, Johann Sebastian Bach. There is an extensive collection of his music in the Bach House in Eisenach, where he was educated and worked. The Psalms and motets that dominate Bach’s extensive repertoire were all influenced by the liturgical reforms of Luther as well as by some of Luther’s own music and hymns. More than any other theologian and reformer, Luther was an important figure in establishing congregational singing as a part of Christian experience. Through Bach we have evidence of the profound changes, in their highest form, Luther brought to arts and culture through sacred music and its vital role in the liturgy.

I am grateful to St. Peter’s congregation for making this educational opportunity possible and to be able to share some personal reflections on my pilgrimage in the steps of this reluctant revolutionary and the people who shared deeply in his life and work. I am also grateful to Lorraine Alexander for her gifts of editing and encouragement to make this paper more engaging to our readers. Happy Anniversary to our reforming ancestors and our heartfelt thanks for helping the faithful rediscover renewing and liberating principles that remain challenges for our own times.

Rev. Canon Albert J. Ogle

Vicar of Lithgow 29th October 2017